Japanese tea house, Chashitsu in Japanese, is where Chado, the tea ceremony takes place, which expresses Japanese sentimentality and aesthetics through the act of drinking tea. It is a rare place you can reflect yourself, feel the connection with nature and others all at the same time.

Table of Contents

Overview of Japanese Tea House

Tea was once consumed as a medicine due to the stimulating effects of caffeine in Japan.

After Zen monks brought tea cultivation from China to Japan during the Kamakura period (1185-1333), the tradition of tea drinking spread to the samurai as well.

The design of free-standing tea houses is heavily influenced by Zen philosophy.

They were built mainly by Zen monks or by daimyo.

(Japanese feudal lord), samurai, and merchants who practiced the tea ceremony.

They sought simplicity and tranquility, the central tenets of Zen philosophy. So, in the past, materials were limited to simple and rustic ones.

Tea ceremonies evolved steeped in Japanese sensibilities concerning nature, and tea houses are spaces that reflect such sentiments.

Today, many practice tea ceremony and enjoy its benefits in numerous types of tea rooms, from traditional ones to innovative ones.

Japanese Tea House Design and Architecture

Japanese tea house, Chashitsu in Japanese, is truly the product of all the traditional Japanese crafts combined and sophisticated.

Usually, the tea house architecture is referred to as the Sukiya-zukuri, which was developed for tea gatherings.

While the style is traditionally simple and uses subdued colors, to build a tea house or tea room, one must enlist the help of a wide variety of highly skilled workers.

The list can start with a carpenter, a thatcher, a plasterer, a fittings craftsman, a tatami maker, and a gardener.

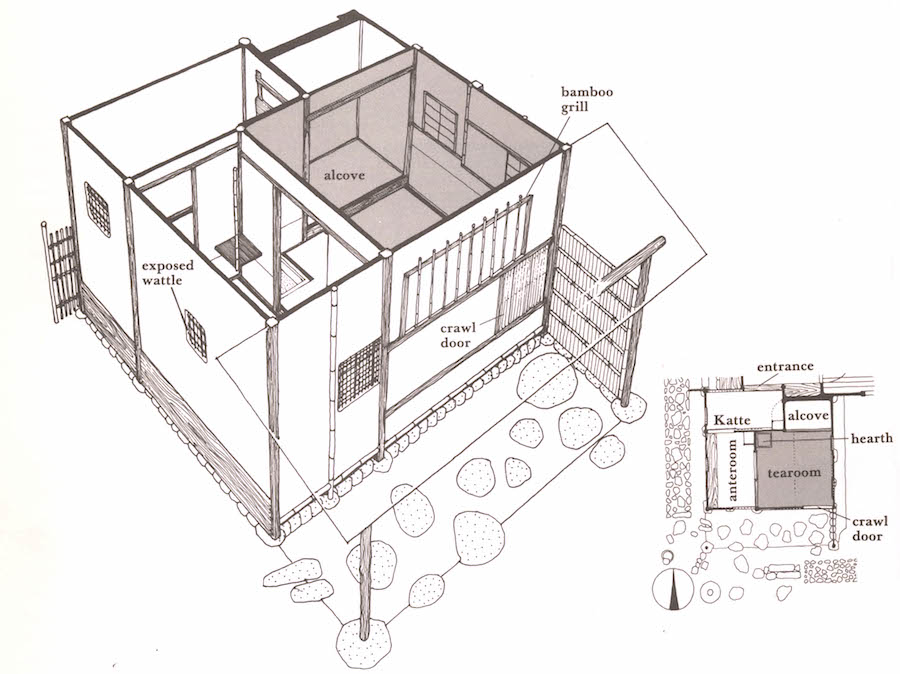

The structure of the Japanese tea house usually consists of two rooms: the mizuya where the host prepares food and snacks and tea supplies are stored, and the other is the main room where tea is served.

Roji (Tea House Garden) – Japanese Tea House

In front of the traditional tea house is a garden called the roji – dewy ground.

Once you step into the garden, you can expect this is going to be something that you can’t experience in the mundane world.

Guests traverse it on a path of stepping stones, admiring the plants and trees. Before entering the tea house building, they are supposed to wash their hands in a stone basin as preparation.

Nijiriguchi (Guest Entrance) – Japanese Tea House

To enter the tea house, one has to crawl through a low and small entrance way called “Nijiri-guchi” regardless of rank, which makes everyone in the house equal.

As the small entryway would force even a great general to leave his sword at the door to pass through, space inside becomes detached from an everyday world with a distance in classes.

It’s designed to make one discard’s title or position and be as pure as when one was born. So, the tea house is often described as the inside of the womb as an analogy.

You may recall the Shinto torii gate and shrines, where visitors are supposed to wash their hands and clean their mouths at the water basin and walk through a gate.

Torii Gate: Boundary between the Profane and the Sacred

Shinto Shrine: History, Architecture, and Shrine Crest

The resemblance is clear, all the settings tell this is not a worldly place, but something out of the world. So one has to clean himself before entering there, which can be seen in Shinto beliefs.

Shinto Beliefs: 5 Core Values of Japanese Indigenous Religion

Japanese Tea House Interior

The ultimate architecture which expresses the spiritual world is the Japanese tea houses.

In Japan, building architecture always has taken consideration of human behavior, buildings are containers while Module, the human measure was adopted in the western world only in the modern times.

Traditional Floor Size – Japanese Tea House

The standard size for a traditional Japanese tea house is 8.2 square meters, four and a half tatami mats.

Japanese rooms are typically measured by the number of tatami mats covering the floor.

The smaller than four and a half tatami mats houses are called “Koma” and larger ones are called “Hiroma”. Each tatami has its name and function.

All doors and windows are traditional Japanese shoji, the sliding doors made of a wooden lattice covered with translucent Japanese paper which allows light from outside to filter into the room.

This extraordinary small room created the space to share the most profound feelings between the host and the guests.

The great variety of bamboo, wood, reed, vines, and straw suggests that such tea houses are created from materials found in nearby forests and fields.

Ro (Hearth) – Japanese Tea House

There is no furniture except for what is required to prepare tea.

Usually, there will be a charcoal pit in the center of the room, and cutting a piece of the tatami is used to boil water.

From November to April, a hearth was installed in the pit. From May to October, the hearth is covered back up with tatami, and a portable stove called a furo is used instead.

Tokonoma (Alcove) – Japanese Tea House

The alcove decorated with a hanging scroll and flowers (cha-bana) is an essential part of the tea house design.

When guests enter the tea house, they first proceed to the alcove to admire the decoration.

Tokonoma: Japanese Alcove Design, Styles, and Scrolls

Ikebana: Styles of Japanese Flower Arrangement “Kado”

The wall of the alcove is plastered and the floor may be wooden paneling or tatami. It is where you can feel connected with nature and its beauty.

Initially, a hanging scroll is hung each morning as one does so with a fresh feeling.

Mizuya (Washing Room) – Japanese Tea House

This is where the host cleans utensils and prepares for a tea ceremony.

Brief History of Japanese Tea House

In 1187, Myoan Eisai, a Japanese priest, traveled to China to study philosophy and religion. When he returned to Japan, he founded Zen Buddhism and built the first temple of the Rinzai sect.

Japanese Buddhism #2: End of the World Belief, Pure Land, and Zen

During the Muromachi period (1336-1573), Japanese architecture went through a transformation from the formal palatial style (Shinden-zukuri) to a simplified style (Shoin-zukuri) favored by the samurai class.

Murata Jukou, the father of the tea ceremony, developed the etiquette and spirit of tea. He studied under Ikkyu Soujun and practiced Zen meditation at Daitokuji Temple.

Jukou preferred the intimate and personal atmosphere of a small room, which could fit five to six people when he served tea to his guests.

His goal was to transcend the complex distractions of the world and find enlightenment in everyday life.

The four-and-a-half tatami mat room that he had devised to create a more tranquil atmosphere during the tea ceremony originated in the Zen philosophy he had studied at Daitokuji Temple.

For the tea ceremony, some of the Shoin-zukuri details were adopted, such as the tokonoma alcove and the side-alcove desk, which would lead to the third style, Sukiya-zukuri, which would produce more varieties of tea houses/rooms.

In 1489, Ashikaga Yoshimasa, the Muromachi shogunate, built Ginkakuji (Temple of the Silver Pavilion) in Kyoto under the influence of Jukou.

The small room in it kept the atmosphere intimate and the host and guests closely connected throughout the ceremony and some consider it the oldest tea room.

Soan Style Tea Room by Rikyu – Japanese Tea House

It was the Wabi-cha tradition that Rikyu perfected after Jukou in the latter half of the 16th century, solidifying the development of Chado.

Chado: “The Way of Tea” Cultivates Hospitality and Zen Spirit

He completed the style by intentionally modeling thatched huts in mountain villages using simple and rustic materials. Extremely narrow tea room, smaller than traditional tea room size with four and a half tatami mats, three or even two tatami mat rooms were created.

Satoyama: Japanese Mindscape of Nature

Typically, Soan tea houses are tiny with roughly cut or completely unmilled wooden timbers. Their rough, earthen walls are made by spreading a mixture of clay and straw over a bamboo lattice.

In such modest structures, seemingly far away from worldly concerns, tea can be enjoyed in a more meditative and philosophical way.

Rikyu taught that this very quality of light was the life of the tea room.

He intended to exclude anything to make his tea room a spot to experience the inner world. Having only a north window keeps the room darker, making utensils look greater and guests to look inwardly.

En-nan Tea Room by Oribe

Furuta Oribe, a successor of Rikyu, developed the new tea room concept, which resulted in a lot of windows designed to be installed purposefully to control the light.

Unlike Rikyu, Oribe made the tea room where you can relax and enjoy the tea ceremony.

Oribe’s tea room was like a stage where the host and guests performed each role. Bold and free, his style is called “Bushi-cha” as well.

The bright tea room had a gorgeous air, making the tea ceremony experience more festive.

Modern Japanese Tea House

Modern architects strive to maintain traditional tea houses’ simplistic beauty while pushing modern interpretations of what a tea house can be.

KOU-AN: Glass Tea House by Tokujin Yoshioka

KOU-AN Glass Teahouse was installed on the stage of Seiryu-den, which is in a precinct of Tendai Sect Shoren-in Temple.

Designed by Tokujin Yoshioka, this project originates from the architectural plan of the Transparent Japanese House, first presented in 2002.

The idea has been developed into a transparent teahouse, an architectural project incorporating a symbolic Japanese cultural image.

KOU-AN is an art piece tracing the origin of Japanese culture that exists in our unconscious sensation by perceiving the time created along with nature.

Tearoom Gyo’an by Shigeru Uchida

It can be folded and reassembled again for the next tea ceremony. Shigeru says it is the typical Japanese ritual style, which enhances the time of the present and makes it even more valuable by folding.

Folded materials can be even more powerful while stored in a storage. It’s believed they recharge the energy.

Lights through the randomly weaved bamboo gives us a sense of openness. Still, this tea house makes us feel we are in a unique secluded place.

Fuan – Floating Tea House by Kengo Kuma

It comprises a helium balloon draped with an ultra-light material called super organza. The fabric works with the pressure of the helium to create a floating structure without walls or pillars.

This absence of crucial building materials points to the simplicity of the structure and makes for the ultimate virtual reality space.

The architect Kengo Kuma talks about his creation, which was initially developed in 2007 as being a space of virtual reality where a state of consciousness in the form of a floating body can exist.

Tea Room by Shingo Takahashi

![茶室 [文彩庵/SHUHALLY] by SHingo Takahashi, Black Tea Room](https://www.patternz.jp/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/茶室-文彩庵/SHUHALLY-Black-Tea-Room-.jpg)

All materials are painted black, which creates a subtle shadowy world.

Shingo thinks it should be an insight for people who live in the modern day to re-examine one’s daily life using familiar materials and techniques with this tea room.

UMBRELLA TEA HOUSE by Kazuhiro Yajima – Japanese Tea House

Fabricated from a single piece of bamboo, this prototype is designed to house the ancient and highly prescribed rituals of the Japanese tea ceremony.

Intended to be easily assembled and dismantled, it originates in the elegance, simplicity, and portability of the traditional oriental parasol.

Reference

茶の湯の始まり (茶の湯の歴史)

茶道の流派 (茶道のみちしるべ)

Related Articles

13 Authentic Japanese Tea Stores in Tokyo

Where to Buy Best Matcha? 5 Established Matcha Stores in Japan

Simplicity and beautiful